Innovation and Disruption Timelines

The speed of disruption matters.

I like to talk about disruption in this newsletter, but one of the things I rarely talk about is the timeline of disruption. Will a disruption take a year, 3 years, or 10 years? How quickly can incumbents react?

All of this matters because it plays a role in who the ultimate winners and losers will be. I’ll get to that in a moment.

First, I want to give a quick update on a busy week ahead for Asymmetric Investing because there’s a lot coming up.

Upcoming Schedule

Thursday, January 29: Innovation and Disruption Timelines

Friday, January 30: New Spotlight Article (Premium)

Saturday, January 31: New Spotlight Article (yes, another one) (Premium)

Sunday, February 1: Sunday Recap Article

Monday, February 2: February Stock Buys (Premium)

Tuesday, February 3: Monthly Live AMA at 10:00 a.m. ET

I’m excited about these spotlights and the risk/reward profile they present long-term.

Disruption Timelines

In 1997, 20% of U.S. households had access to the internet.

A dozen years later, owners of iconic newspapers like the Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, Philadelphia Inquirer, and many more had filed for bankruptcy.

Disruption came quickly for newspapers once publishing online became trivial.

Contrast that to streaming, which has taken much longer to disrupt traditional TV and film media. Netflix launched streaming in 2007, and 19 years later, one of the companies that should have been disrupted the most, Warner Bros Discovery, is being acquired by Netflix itself for $83 billion.

Disruption happens at different speeds in different industries, and there are good reasons why. Different industries have different:

Barriers to entry

Switching cost

Ability for incumbents to respond

Take the media business as a great example. The gating factor wasn’t what people wanted to consume that determined the timeline of disruption; it was the size of the files being passed around.

It took a decade for the internet to hollow out the newspaper business (text) and a few years longer for music to catch up, although much of the legacy industry is still intact, even if it looks different than it did.

20 years after Netflix launched streaming, incumbents like HBO, Disney, NBC Universal, and others are not only still in business, but they’re extremely valuable and growing their own streaming services.

A similar dynamic has happened in the auto business.

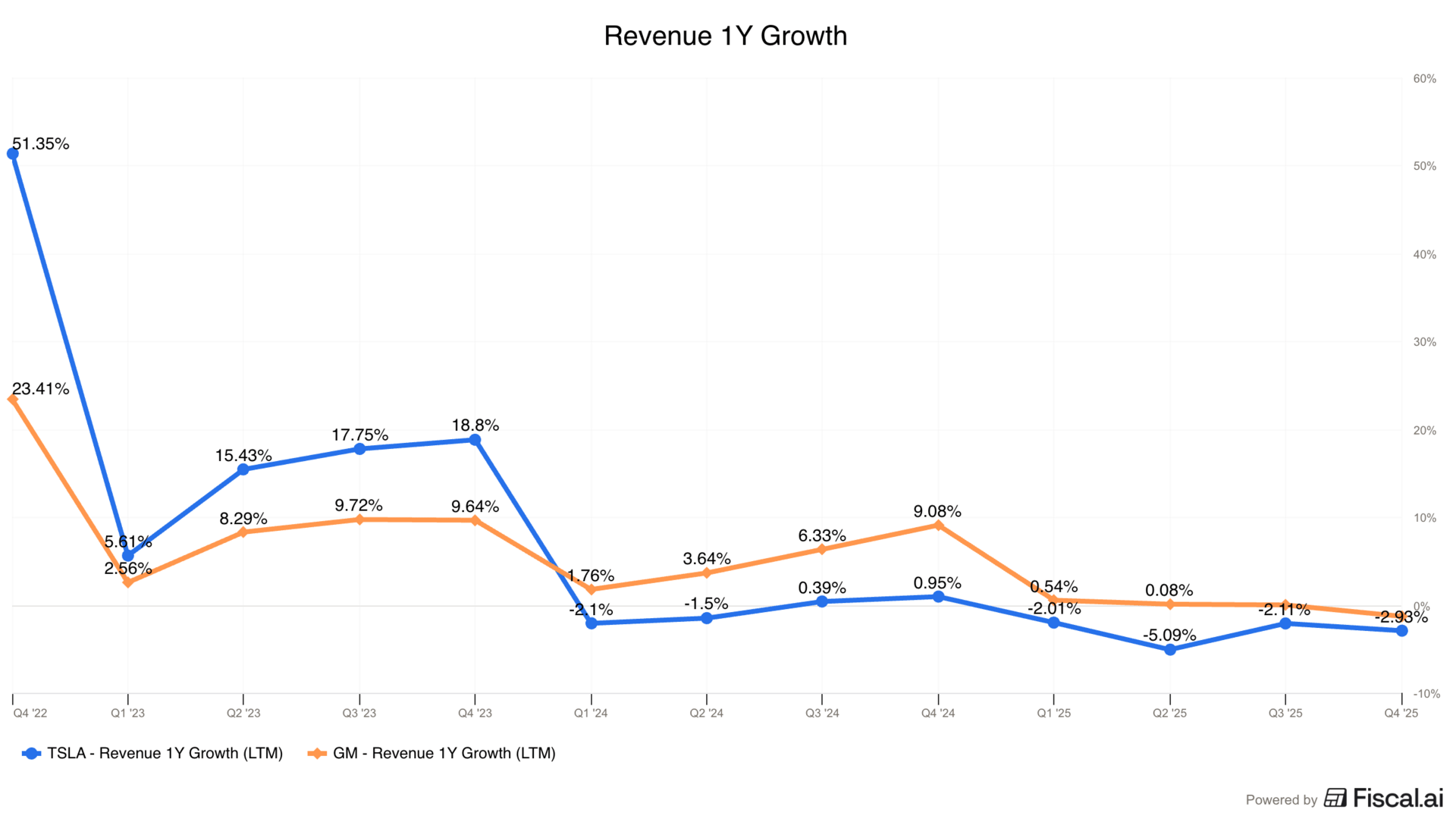

I write this in the same week that Tesla, which was supposed to bankrupt the traditional auto industry, reported negative revenue growth and another decline in margins.

Disruption came for the auto industry, but the long timeline to design a car, build a factory, build brand awareness and distribution, and ultimately generate sales was so long that incumbents could respond.

GM not only fended off Tesla, but it’s also now growing faster than Tesla, the once disruptor.

How Incumbents Respond

When we look at disruption, we have to ask three key questions.

Can incumbents respond?

Will incumbents respond?

Do incumbents have time to respond?

The answer for each will depend on the industry. I’ll highlight how I look at disruption in the auto, medical, housing, and financial industries.

Auto Industry: In the auto industry, for example, incumbents can respond and have lots of time to respond because factories take time to build and an automobile purchase is made every few years, at most. The question is, will they respond?

Medical Industry: Doctors, pharmacies, medical device companies, and insurers are all intertwined in an industry that makes it nearly impossible for incumbents to respond or be willing to respond. Disruption will take time, but I doubt incumbents will have the ability to react even when they see disruption coming.

Housing Industry: What companies like Zillow are disrupting in the housing industry is the local monopoly that agents have on a market. Given the existing structure, agents have little ability to respond and are incentivized to be unwilling to respond (why cut commissions from 6% to 1% if you don’t have to?), despite having ample time to adapt to a digital paradigm.

Financial Industry: Can credit card companies give up a 3% fee in order to stave off disruption from the blockchain and stablecoins? I think they can, but won’t, given their profit motivations, and by the time they do, it’ll be too late.

Investing in disruptors that can disrupt is important for investors. If incumbents can and are willing to respond, innovation may just sustain the incumbent’s power (see Google and OpenAI).

The Takeaway

As investors, we need to understand how disruption works in a given industry.

If incumbents can respond and there’s ample time for them to do so, it’s not an attractive industry.

But if incumbents are unwilling and unable to react to disruption, there’s a real opportunity for investors.

The timeline of that disruption is important to understand because it may tell us there’s a different constraint than just having an innovative product.

That’s the sweetspot I’m trying to find.

Disclaimer: Asymmetric Investing provides analysis and research but DOES NOT provide individual financial advice. Travis Hoium may have a position in some of the stocks mentioned. All content is for informational purposes only. Asymmetric Investing is not a registered investment, legal, or tax advisor, or a broker/dealer. Trading any asset involves risk and could result in significant capital losses. Please, do your own research before acquiring stocks.