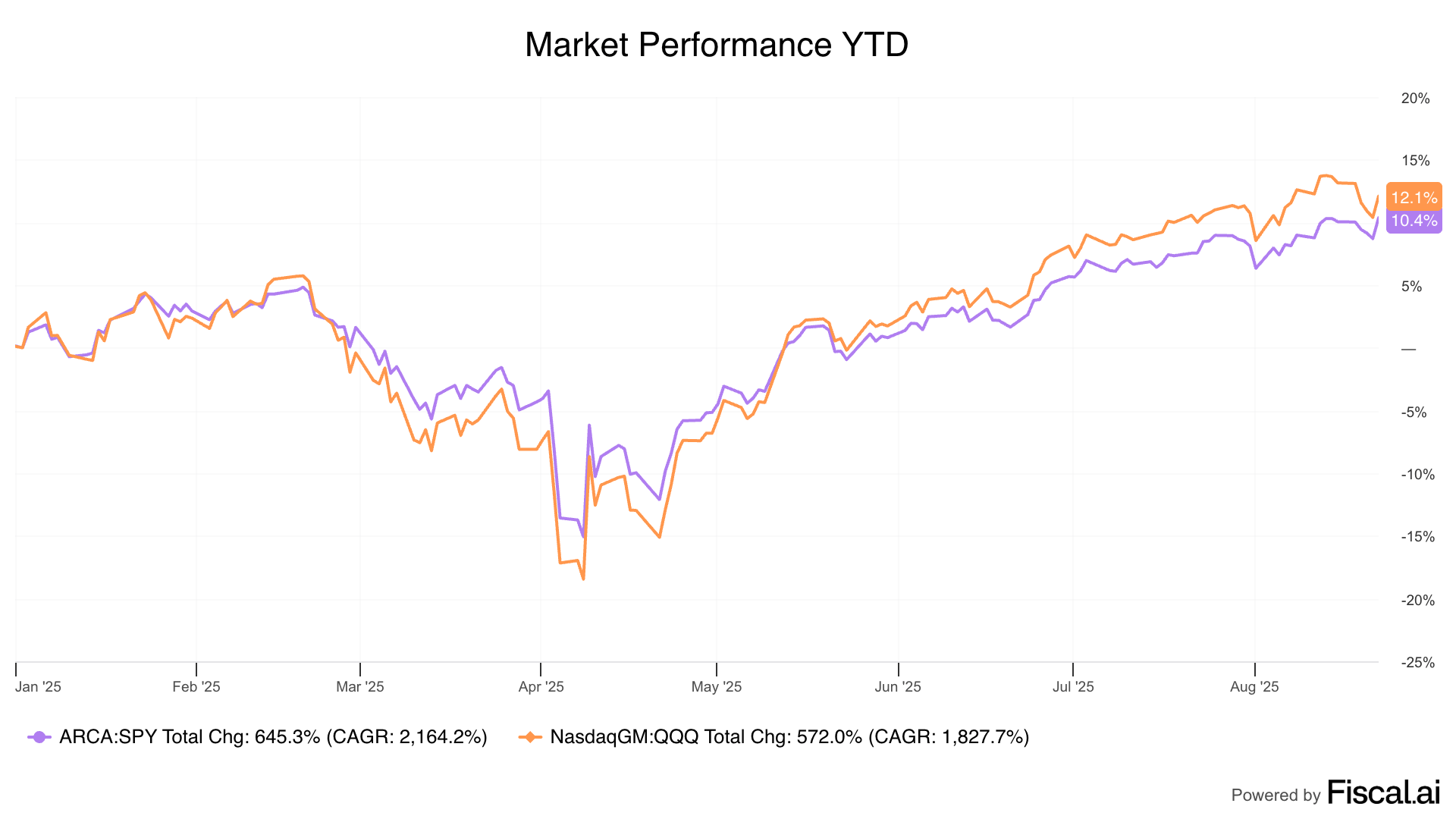

The stock market went a little crazy on Friday after Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell all but stated interest rates would be cut at their September meeting.

Investors think lower rates are good for the markets, and in some ways that’s true. A lower discount rate means assets (stocks) are more valuable, and obviously, that’s what we saw on Friday.

But the reason Powell is open to lowering rates should be getting more attention. He pointed out that GDP growth is slowing, unemployment is rising, and while that would normally make lower rates an obvious answer, we need to balance against inflation, which is also picking up.

What’s next? I’ll try to put some perspective on interest rates and the future of inflation, and the stock market below.

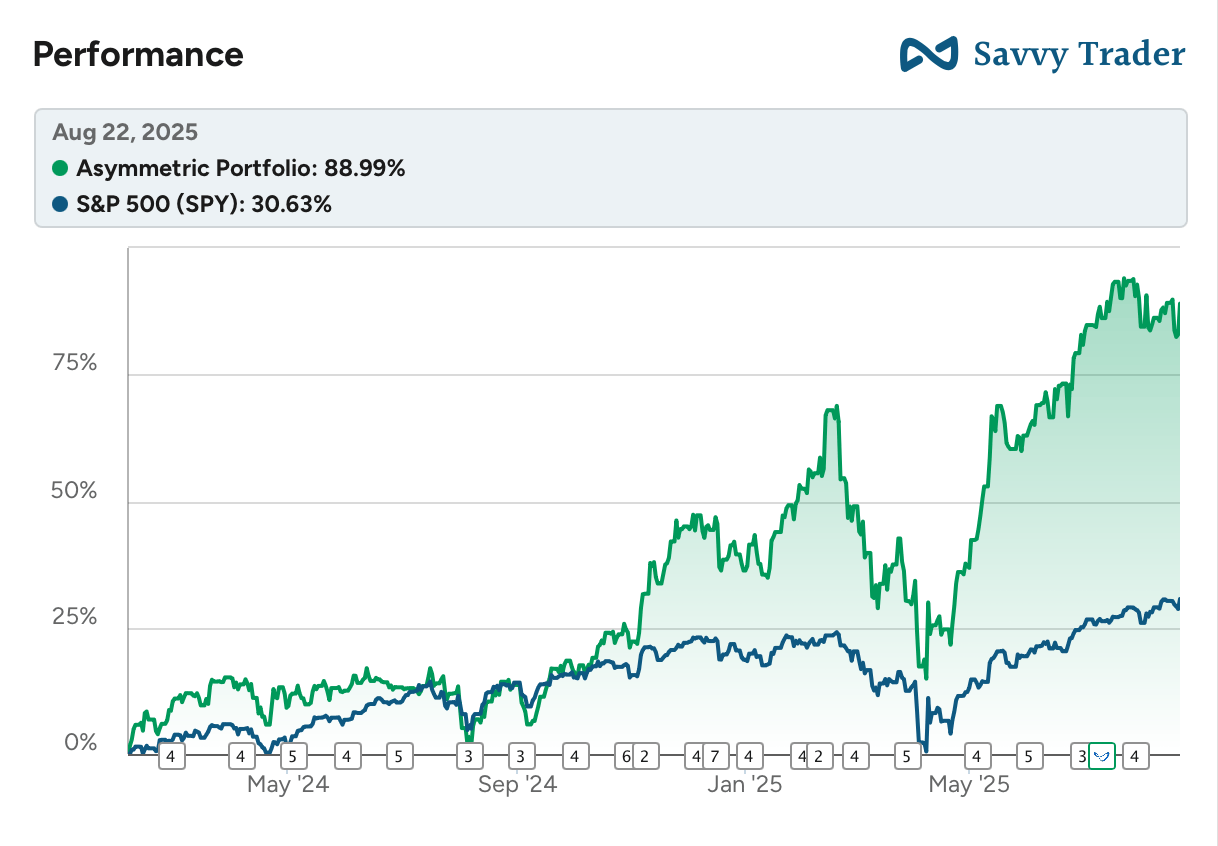

The Asymmetric Portfolio continues to bounce around, recovering sharply on Friday. I’m not going to complain about the gains, but I’m also aware that some of the more highly valued stocks in the portfolio could drop dramatically if there’s an economic downturn.

The Fed & Markets

Outside of times of financial crisis, I can’t remember a time when this many people have an opinion about what the Federal Reserve should do.

They should cut rates.

They should hold rates steady.

Jerome Powell is brilliant.

Powell is a moron.

Everyone seems to have an opinion. But let’s take a step back and look at what the Fed actually does, why, and what the Fed doesn’t do.

What the Fed Does

The Fed sets short-term interest rates, known as the Fed Funds Rate.

The fed funds rate can be accessed by certain institutions outlined in the quote below.

The market sets long-term rates, but they’re set based largely on speculation about future short-term rates (sometimes this is correlated with the Fed’s move, and sometimes it’s not).

There’s a “dual mandate” for the Fed — keep unemployment low and keep inflation in check.

“Full employment” is the goal.

2% was the former target inflation rate, although Powell brought that into question with his speech on Friday, indicating they would be more flexible about the rate.

The fed funds rate isn’t something you or I could access, but banks can:

The federal funds market consists of domestic unsecured borrowings in U.S. dollars by depository institutions from other depository institutions and certain other entities, primarily government-sponsored enterprises.

What’s important to understand is how the Fed impacts long-term rates because the Fed doesn’t really set the 5, 10, 20, or 30-year rate for government bonds, mortgages, or anything else. But that doesn’t mean they’re not important.

The Fed only sets short-term rates, which end up being a starting point for the yield curve for bonds.

Over the past two decades, the Fed has impacted long-term rates more than normal by buying longer-term debt (government bonds and, at times, corporate and mortgage debt), which was known as quantitative easing (QE).

The Fed didn’t “print money” per se; they bought debt, effectively increasing the amount of money outstanding.

This also created what was known as the “Fed put”, which traders used to say the Fed would buy bonds if yields got too high. In other words, investors could dump debt onto the Fed if all else failed.

In recent years, the Fed has been reducing the assets it owns, which is known as quantitative tightening, slowly unwinding #2.

This dynamic leads to a complicated market. In general, short-term rates will move along with the speculation about the next few months of Fed moves.

But long-term rates can be impacted by everything from the Fed funds rate to inflation to tariffs, and much more.

In short, the Fed controls short-term rates, but doesn’t control long-term rates. Those are still controlled by the market.

How the Fed Impacts Markets

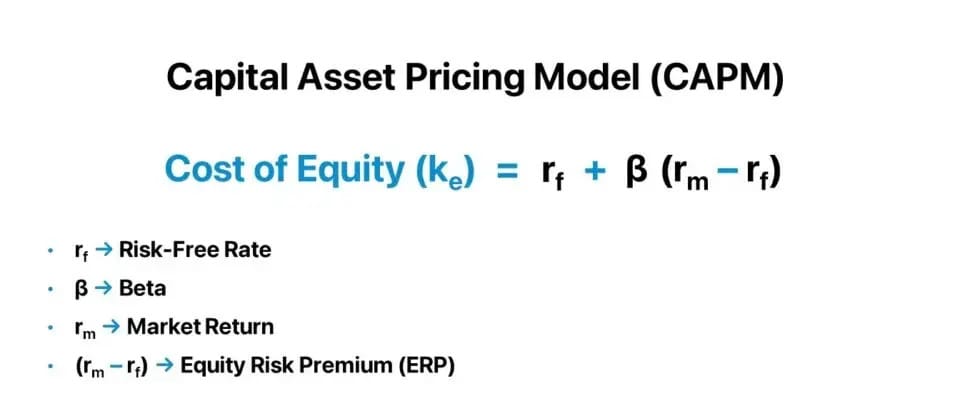

The reason investors watch the Fed so closely is that the Fed impacts how assets are priced.

In financial theory, future cash flows for a business are discounted back to present value using the capital asset pricing model, which uses the fed funds rate as the risk-free rate (rf below). If rf goes down, the value of all assets goes up.

That’s why the market cares.

I could spend thousands of words breaking down why this model is extremely flawed, but that’s the theory behind the short-term market move.

Why Rates Go Up

With that background out of the way, we need to ask why rates have gone up over the last few years.

The easy answer is inflation.

The Fed doesn’t want inflation to get too high, and higher rates are the best tool to fight inflation. They do this by slowing down the economy.

Low rates are seen as fuel for the economy and inflation.

If you want an example, look at the value of housing during 2020 and 2021, fueled by low rates. The only way to slow the market was to raise rates.

Why Rates Go Down

Every politician wants the Fed to cut rates because lower rates boost the economy (making it cheaper for businesses to borrow money and easier for people to get mortgages), but the Fed typically cuts rates because it sees a weak economy.

Since 1985, every major sustained decline in rates has corresponded with a recession and — you guessed it — a market crash.

I want to be clear about this. The Fed doesn’t cut rates because the economy is going gangbusters. It cuts rates because the economy is doing poorly and needs a little fuel.

One rate cut isn’t alarming and doesn’t mean a crash is coming.

It may just be an adjustment within a “range” of appropriate rates.

And we aren’t in a steep declining rate environment yet.

But if we start talking about multiple rate cuts that’re happening because the economy is bad…historically, that’s bad news for stocks.

What Powell Really Said on Friday

I’m going to start with Powell’s direct quotes.

On employment:

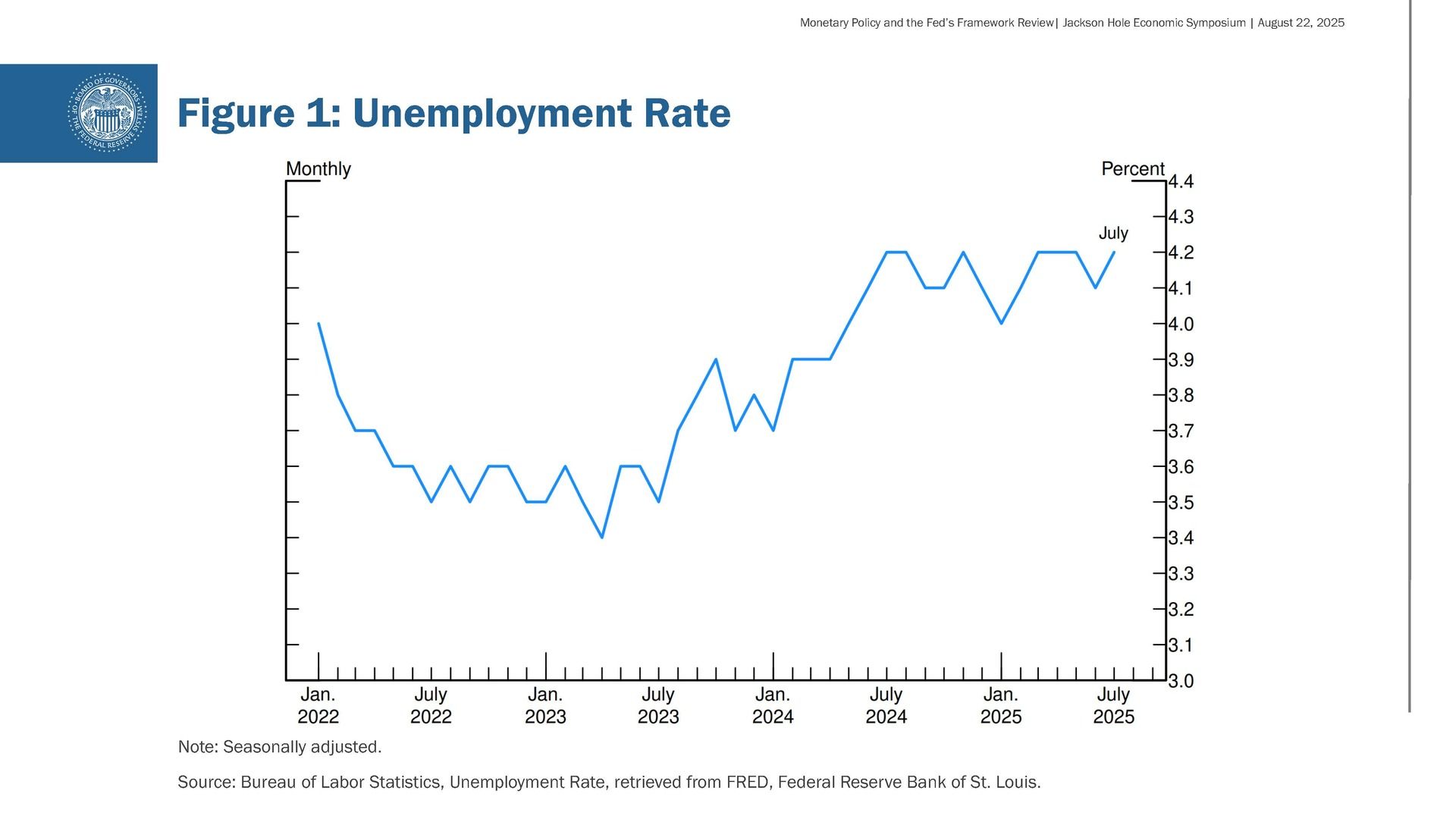

The July employment report released earlier this month showed that payroll job growth slowed to an average pace of only 35,000 per month over the past three months, down from 168,000 per month during 2024. This slowdown is much larger than assessed just a month ago, as the earlier figures for May and June were revised down substantially. But it does not appear that the slowdown in job growth has opened up a large margin of slack in the labor market—an outcome we want to avoid. The unemployment rate, while edging up in July, stands at a historically low level of 4.2 percent and has been broadly stable over the past year. Other indicators of labor market conditions are also little changed or have softened only modestly, including quits, layoffs, the ratio of vacancies to unemployment, and nominal wage growth. Labor supply has softened in line with demand, sharply lowering the "breakeven" rate of job creation needed to hold the unemployment rate constant. Indeed, labor force growth has slowed considerably this year with the sharp falloff in immigration, and the labor force participation rate has edged down in recent months.

Overall, while the labor market appears to be in balance, it is a curious kind of balance that results from a marked slowing in both the supply of and demand for workers. This unusual situation suggests that downside risks to employment are rising. And if those risks materialize, they can do so quickly in the form of sharply higher layoffs and rising unemployment.

On inflation:

The effects of tariffs on consumer prices are now clearly visible. We expect those effects to accumulate over coming months, with high uncertainty about timing and amounts. The question that matters for monetary policy is whether these price increases are likely to materially raise the risk of an ongoing inflation problem. A reasonable base case is that the effects will be relatively short lived—a one-time shift in the price level. Of course, "one-time" does not mean "all at once." It will continue to take time for tariff increases to work their way through supply chains and distribution networks. Moreover, tariff rates continue to evolve, potentially prolonging the adjustment process.

It is also possible, however, that the upward pressure on prices from tariffs could spur a more lasting inflation dynamic, and that is a risk to be assessed and managed. One possibility is that workers, who see their real incomes decline because of higher prices, demand and get higher wages from employers, setting off adverse wage–price dynamics. Given that the labor market is not particularly tight and faces increasing downside risks, that outcome does not seem likely.

Another possibility is that inflation expectations could move up, dragging actual inflation with them. Inflation has been above our target for more than four years and remains a prominent concern for households and businesses. Measures of longer-term inflation expectations, however, as reflected in market- and survey-based measures, appear to remain well anchored and consistent with our longer-run inflation objective of 2 percent.

Of course, we cannot take the stability of inflation expectations for granted. Come what may, we will not allow a one-time increase in the price level to become an ongoing inflation problem.

Putting it all together:

Putting the pieces together, what are the implications for monetary policy? In the near term, risks to inflation are tilted to the upside, and risks to employment to the downside—a challenging situation. When our goals are in tension like this, our framework calls for us to balance both sides of our dual mandate. Our policy rate is now 100 basis points closer to neutral than it was a year ago, and the stability of the unemployment rate and other labor market measures allows us to proceed carefully as we consider changes to our policy stance. Nonetheless, with policy in restrictive territory, the baseline outlook and the shifting balance of risks may warrant adjusting our policy stance.

The takeaway here is pretty clear. Unemployment isn’t a problem, not because there are lots of jobs, but because there’s less labor due to fewer immigrants.

Inflation, on the other hand, appears to be heading higher, but Powell views this as a one-time impact, rather than a structural change in the rate of inflation.

The Translation

One of the challenging aspects for investors is the interplay between low interest rates, economic growth, and inflation.

Lower rates = GOOD

Slow GDP growth = BAD

Inflation = BAD

The inflation angle is the most interesting. We’re already seeing companies like Walmart and Target talk about customers trading down to save money. So, consumers are price sensitive.

We also know the cost of importing some goods is going up.

Is there an ability to pass higher costs on to customers? Maybe in some cases. But not across the board.

The alternative is for someone in the supply chain to eat the higher cost. That’s suppliers, product companies, or retailers.

If tariff costs can’t be passed on, that would mean lower margins and lower profitability for many companies.

This is what I’m worried about.

The next year or two is OK on the top line, but profits take a hit. And does the market deserve its current valuation if profits start to decline?

For now, the market is seeing roses in a potential rate cut in September.

But let’s remember the Fed doesn’t cut rates when everything is going great. They cut when the economy needs a boost, and that’s not necessarily good for stocks over the next few months or years.

Disclaimer: Asymmetric Investing provides analysis and research but DOES NOT provide individual financial advice. Travis Hoium may have a position in some of the stocks mentioned. All content is for informational purposes only. Asymmetric Investing is not a registered investment, legal, or tax advisor, or a broker/dealer. Trading any asset involves risk and could result in significant capital losses. Please do your research before acquiring stocks.