I'm fully focused, man, my money on my mind

Got a mil' out the deal and I'm still on the grind

On February 6, 2003, 50 Cent released his debut album Get Rich or Die Tryin’, which included these iconic lyrics.

How exactly did 50 Cent have $1 million before releasing his first record?

When 50 Cent signed a record deal with Dr. Dre and Eminem’s label in 2002, he netted a $1 million payment before recording the album, much less releasing it. In return, 50 Cent gave up a vast majority of the royalties associated with album sales.

The scale of 50 Cent’s deal is unusual, but the structure isn’t. Record labels use big advances to attract talent and seduce them to sign deals that will ultimately benefit the label more than the artist. And this tension came to a head last week when Spotify became a target of a fair pay bill in the U.S. House of Representatives.

This week’s post is sponsored by The Rundown AI.

The Rundown is the world’s fastest-growing AI newsletter, with over 500,000+ readers staying up-to-date with the latest AI news and learning how to apply it.

Our research team spends all day learning what’s new in AI, then distills the most important developments into one free email every morning.

Spotify Under Attack

On March 7, representatives Rashida Tlaib and Jamaal Bowman introduced a bill called the Living Wage for Musicians Act that calls “for economic justice and fairness in streaming.”

The bill aims to force streaming services to pay $0.01 per stream, up from an average of about $0.003 per stream today. Tlaib said it takes 800,000 streams per month for an artist to make minimum wage of $15 per hour and apparently thinks the appropriate number of streams is 240,000 to make $15 per hour. 🤷

For perspective, $0.01 per stream would mean today’s $11 subscription would only allow a user to listen to 769 songs per month, or about 1 hour and 15 minutes per day (assuming 3-minute songs). It would also make ad-supported music untennable.

The proposal isn’t likely to become law, but it highlights how few people realize what a boon the streaming industry has been in music and how the economics of music and streaming work.

Attacking the Savior

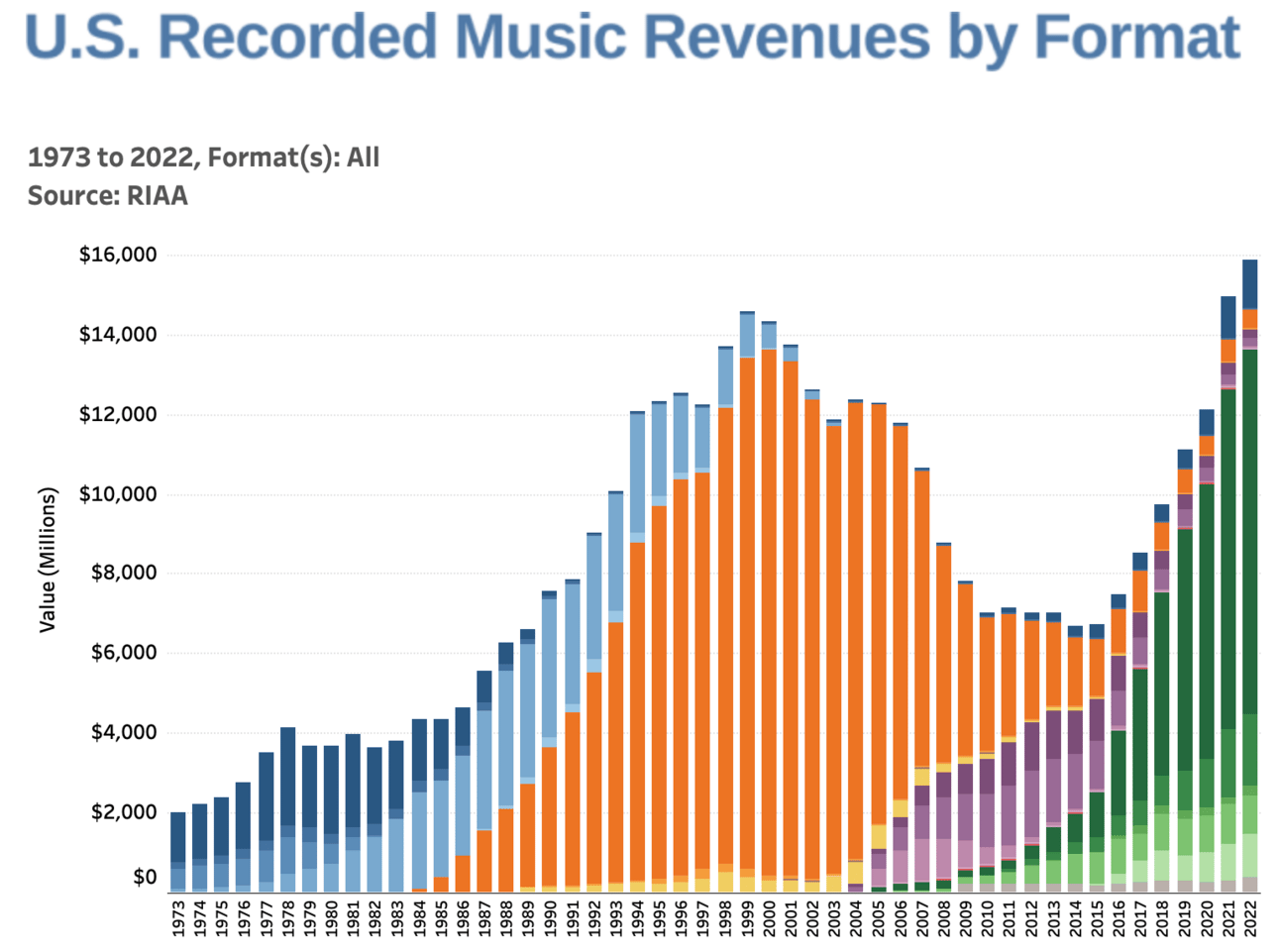

The truth is, the subscription and ad-supported streaming model developed by Spotify saved the music industry. According to RIAA, in 2014 and 2015 the U.S. record industry generated just $6.7 billion in revenue, a figure that more than doubled to $15.9 billion in 2022.

At the center of that growth was streaming music and specifically, Spotify. Premium subscriptions accounted for $9.2 billion in revenue and ad-supported was $1.8 billion in revenue. CDs (in dark orange below), which used to dominate the industry, were less than $500 million in revenue.

Streaming revenue is in dark green. Source: RIAA.

However, the fact that streaming has grown the pie is lost on most in the industry.

Snoop Dogg is upset about getting $45,000 for 1 billion streams on Spotify. And it when you put it that way the structure seems unfair. But there might be more to the story…

What Snoop Dogg conveniently leaves out is that he disclosed the check he got for 1 billion streams, based on what his publisher told him. But the total Spotify paid for those streams was likely many multiples higher than $45,000 and Snoop Dogg only gets a fraction of what Spotify paid out because of deals he signed decades ago.

Who Gets Paid For Hits?

Artists often sign long-term record deals that only pay out if hits are made. I don’t mean only pay out big — I mean many artists don’t make a dime on music sales unless they make a hit song or album!

Artists are induced by big advances (see 50 Cent’s $1 million “out the deal”) and they give up 85% to 95% of future record revenue for that upfront check, which needs to be repaid...

Advances: Lump sums of money (usually cash) given to an artist when they sign a record deal (aka Execution), marking the start, or Commencement, of the Initial Period, or when they begin a subsequent project period, marketing the start of an Option. It’s common to see an advance split into parts, e.g. 50% paid upfront and 50% paid after delivering the required EP or LP.

Artist royalties are paid after the advance has been repaid and after any other bills are paid. For example, if you pay Pharrell Williams $100,000 to produce a song, that needs to get paid back before the artist gets paid.

Artist Royalties: Your cut of revenue from streams, downloads, CDs, etc. Royalty rates can vary by territory (e.g. a higher rate for domestic sales and a lower rate for international sales) and won’t hit your bank account if you have an unrecouped balance (if your royalties haven’t paid back your advance and budgets). It’s standard for acts to receive around 15% of revenue in traditional deals

You can see how the industry can seem unfair when artists point out their streaming check. But this is a little like a football player demanding a huge signing bonus only to complain about their base salary in the last year of the deal.

For labels, the business model is to sign a large number of artists, knowing that most of them won’t even earn back their advance. Every once in a while, the artist becomes Snoop Dogg or Taylor Swift, generating hundreds of millions of dollars in value for the label. But they’re the outlier, not the norm.

Spotify Can’t Change the Record Industry…It Tried

Artists could forego the record deal structure, posting content directly on Spotify. But that would mean no advance, no marketing budget, no producer, no infrastructure.

Jay-Z did this, starting his own label and self-funding his first album, which is why he’s a billionaire today. He owns his music. Most artists choose to go the safe route and sign with a label.

If Snoop Dogg wanted to make $3 million on a billion streams instead of $45,000, he needs to own the label. He partially did that in 2022, buying the Death Row brand, but there haven’t been reports he has acquired any of the music rights, including his own. His complaint stems from a deal he signed more than 30 years ago.

Taylor Swift has been caught up in this as well. Her “master recordings” were sold in 2020 for a reported $300 million (likely more than Swift has ever made directly from music sales like CDs or streaming) and this ultimately led to her re-recording “Taylor’s Version” of albums, which Swift owns.

In most of these disputes, Spotify is just the middleman between the customer and the label with artists getting paid after everyone else. But this was the case with cassettes, CDs, and music downloads as well.

Music on Spotify earns two kinds of royalties:

Recording royalties: The money owed to rightsholders for recordings streamed on Spotify, which is paid to artists through the licensor that delivered the music, typically their record label or distributor.

Publishing royalties: The money owed to songwriter(s) or owner(s) of a composition. These payments are issued to publishers, collecting societies, and mechanical agencies based on the territory of usage.

When an eligible song gets played on Spotify, the rightsholders receive royalties for it, whether it’s played by a Premium or ad-supported customer.

We know that about 70% of Spotify’s revenue is paid out to record labels. And that’s based on what tier the stream is played on.

We distribute the net revenue from Premium subscription fees and ads to rightsholders. To calculate net revenue, we subtract the money we collect but don’t get to keep. This includes payments for things like taxes, credit card processing fees, and billing, along with some other things like sales commissions. From there, the rightsholder’s share of net revenue is determined by streamshare.

We calculate streamshare by tallying the total number of streams in a given month and determining what proportion of those streams were people listening to music owned or controlled by a particular rightsholder.

Contrary to what you might have heard, Spotify does not pay artist royalties according to a per-play or per-stream rate; the royalty payments that artists receive might vary according to differences in how their music is streamed or the agreements they have with labels or distributors.

Here’s what I think everyone loses in this discussion.

Streaming music lives by what I call internet economics. There’s essentially zero marginal cost to deliver each incremental stream, so the best financial decision economically is to maximize revenue by maximizing the number of streams overall.

Put it this way, is it better to get $0.10 per stream on 10,000 streams ($1,000) or $0.001 per stream on 10 million streams ($10,000)?

Obviously, the latter, especially when artists make most of their money on tour. But no one wants to admit this reality.

Spotify and Apple Music also don’t set their prices in a vacuum. The price for premium music streaming is part of negotiations with record labels, so the labels are just as responsible for setting the appropriate price to maximize overall industry revenue as Spotify is.

Everyone’s incentive is to maximize the overall revenue of the industry overall. Or do we honestly think they could raise prices 100% and no one would cancel?

Internet Economics Strikes Again

What’s frustrating watching the Spotify discussion is the fact that no one acknowledges the reality of the music industry today.

Streaming, like the internet, lowers per unit revenue but maximizes overall value because there’s zero marginal cost. The alternative is to distribute music off Spotify and other streamers.

That’s proven to be a bad strategy by artists bigger than Snoop Dogg.

Taylor Swift pulled her music from Spotify in 2014 over a dispute about how much she was being paid and who could listent to her album (she wanted a premium-only release). She returned to Spotify in 2017.

Niel Young pulled his music in 2020 only to return earlier this year.

In each case, they came back to Spotify because they needed Spotify more than Spotify needed them. If you’re Swift, how do you make $1 billion on tour if people haven’t heard your music?

Spotify is essential for artists to reach fans, whether streaming music is a moneymaker or not. But we also need to acknowledge that Spotify and streaming have grown the pie for artists.

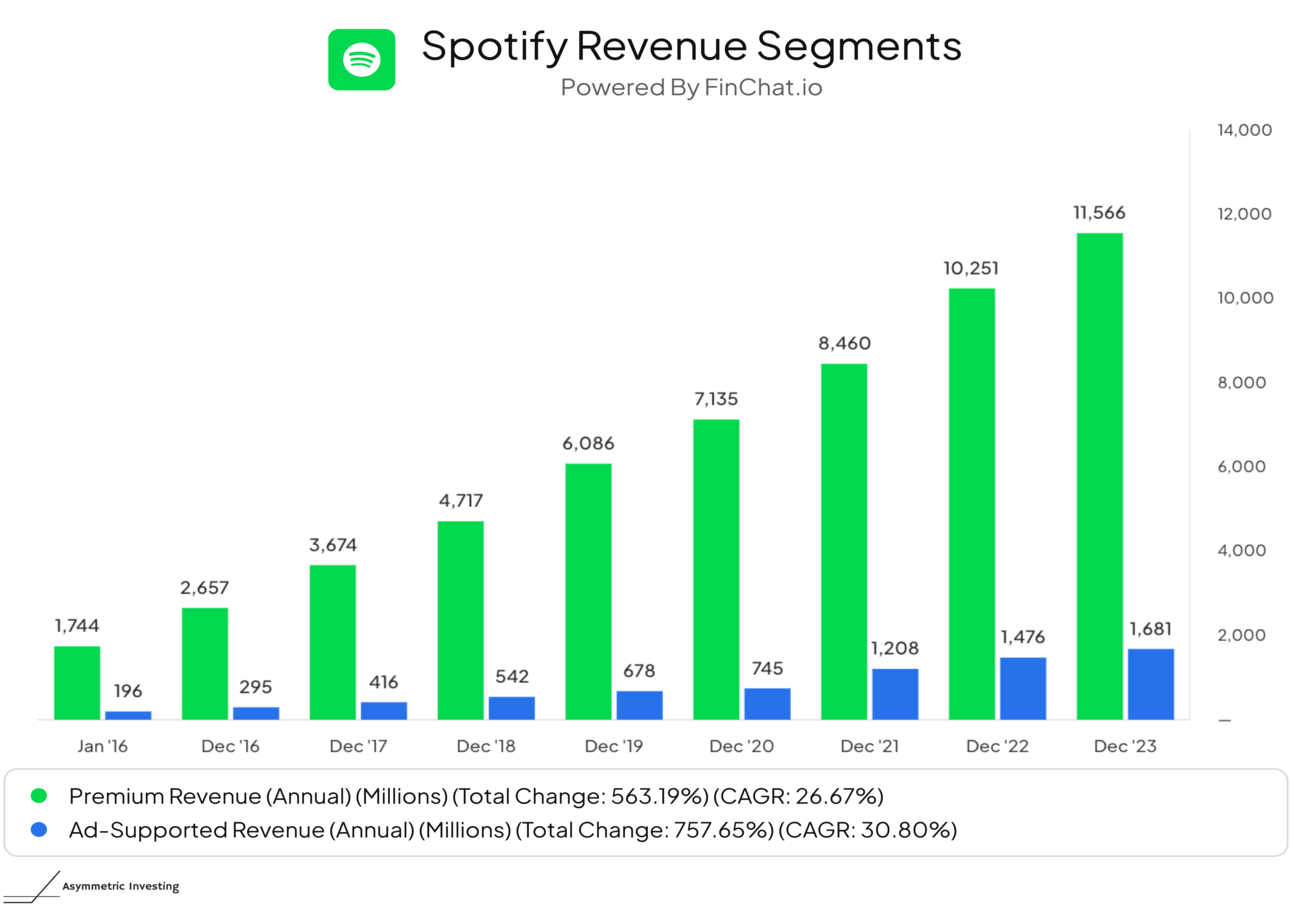

What Congress and artists should want is for Spotify to generate more revenue on the ad-supported tier, which has 379 million subscribers to 236 million premium subscribers, and generates a fraction of the revenue.

But Spotify also needs an ad-supported tier as the top of the funnel for the much more economical premium tier. You can’t have one without the other.

To make ads work better for artists, Spotify is investing billions to develop the ad tech, attract advertisers, target ads effectively, and ultimately grow the business. And doesn’t Spotify deserve to make a profit for this investment?

Saying artists should make more money is easy.

Building the technology and business model that has driven the record industry to new heights is hard.

I only wish the public discourse included the nuance that’s needed to understand the business model and tradeoffs that make music, podcasts, and now audiobooks viable for artists.

The other option is to brute force a bill through that will cause Spotify to raise premium subscription prices to $35/month and end ad-supported streaming for millions of Americans.

Business models matter. And decisions have consequences.

Disclaimer: Asymmetric Investing provides analysis and research but DOES NOT provide individual financial advice. Travis Hoium may have a position in some of the stocks mentioned. All content is for informational purposes only. Asymmetric Investing is not a registered investment, legal, or tax advisor or a broker/dealer. Trading any asset involves risk and could result in significant capital losses. Please, do your own research before acquiring stocks.